Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (290)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (1)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (3)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1880s (10)

- 1890s (29)

- 1900s (8)

- 1910s (138)

- 1920s (219)

- 1930s (33)

- 1940s (35)

- 1950s (15)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1860s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1960s (0)

- 1970s (0)

- 1980s (0)

- 1990s (0)

- 2000s (0)

- 2010s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (43)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (5)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (1)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (6)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (2)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (2)

- Qualla Boundary (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (88)

- Asheville (N.C.) (0)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (85)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (15)

- Envelopes (37)

- Glass Plate Negatives (5)

- Letters (correspondence) (366)

- Manuscripts (documents) (273)

- Maps (documents) (3)

- Memorandums (1)

- Photographs (195)

- Portraits (1)

- Postcards (5)

- Publications (documents) (6)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Interviews (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Sound Recordings (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Transcripts (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (729)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

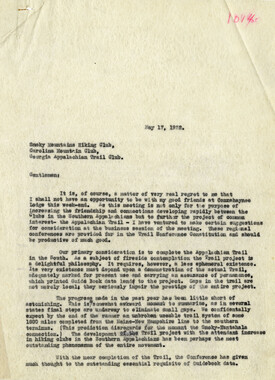

- Appalachian Trail (6)

- Forest conservation (2)

- Forests and forestry (5)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (18)

- Hunting (7)

- Maps (2)

- Mines and mineral resources (3)

- Postcards (1)

- World War, 1939-1945 (4)

- African Americans (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Storytelling (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- StillImage (296)

- Text (647)

- MovingImage (0)

- Sound (0)

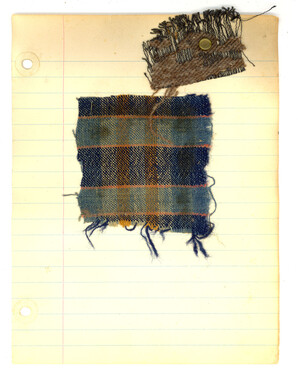

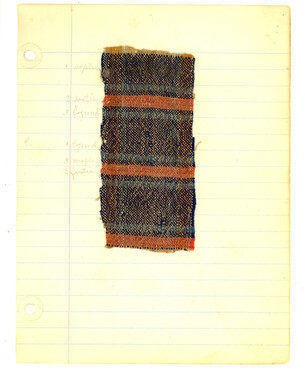

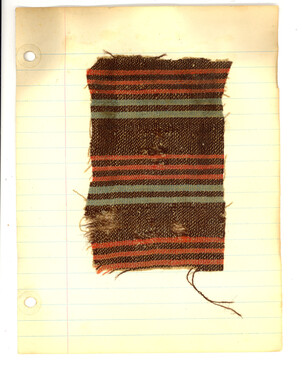

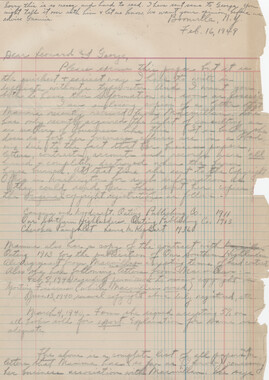

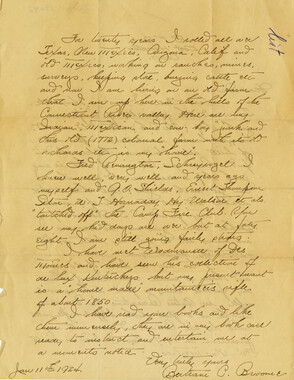

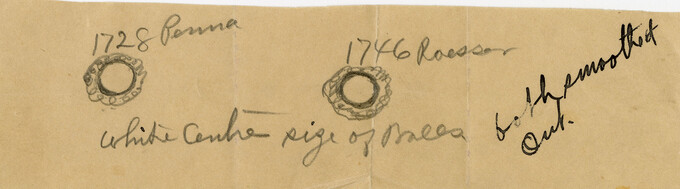

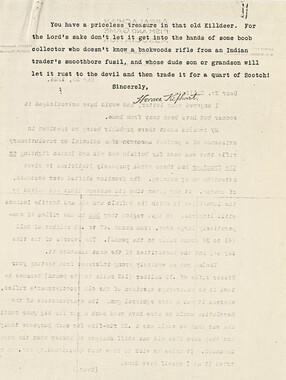

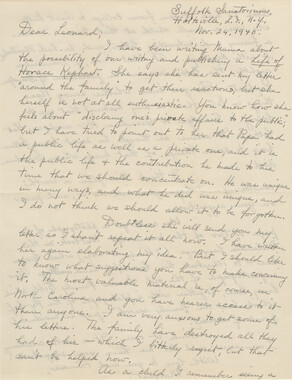

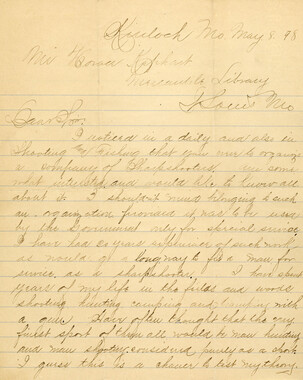

Horace Kephart Journal 19

-

Horace Kephart (1862-1931) was a noted naturalist, woodsman, journalist, and author. In 1904, he left St. Louis and permanently moved to western North Carolina. Living and working in a cabin on Hazel Creek in Swain County, Kephart began to document life in the Great Smoky Mountains. He created 27 journals in which he made copious notes on a variety of topics. Journal 19 (previously known as Journal IX) includes information on characteristics of people in general. Click the link in the Related Materials field to view a table of contents for this journal.

-

-

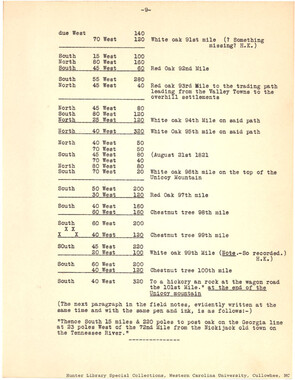

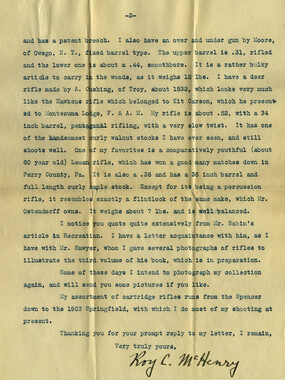

I CHARACTER- Def inition. Character is the combinat1on of qualities distinguishing any person or class of persons~ any d1stinctive mark or trait, or such marks and tro.its collectively, ·belonging to any person, class. or race; the individuality which is t 1e product of nature, habits. and environment. (St. Diet.) j The sum of those mental and moral qualities which distinguish a human being as a personality. (Enc. Brit.) Personality includes the physical qualities. Character and Plot ~~~"""~~~~~~~l""~IGHBROWS of "\l all time have ~ exercised their H j analytic powers on the relative ( importance, in 1'o .. President lt~r CollieT' s faT next 1u. ~~L:)11111~~~~-~j~5 literature, of character, plot, and style. Reading 1:) an exciting detective story the other day, to soften the hours between dinner and an upper berth, we ,,·ere Htruck anew with the necessity of characterization to make the most of plot, even in narrative which especially depends most upon suspense. ''The .L\lystery of the Yellow Room'' has a plot superior to the majority of those through which moves the figure of l\Ir. Sherlock Holmes; the writing is at least not inferior; the total effect, nevertheless, falls far short, for the one reason that nobody stands out as a vividly created being. The l<'renchman 's tale, once begun, can not be dropped by any reader addicted to such fare, but is laid aside at the end without that regretful intimacy which the Doyle detective leaves at his fleparture. l\Iost of us can agree with ARISTOTLE, that the rarest and highest element in literature is a first-rate story adequately unfolded, but the story, or plot, or fable, in that sense, implies character; there is no really great tale that is not rich in human meaning. There may be gorgeous language and entrancing personages, as in "The l\Ierchant of Venice" or "Henry V," with no great truth or beauty in the story's outline. There is in the nature of things no great plot conceivable unless the personages through whom it lives are also greatly drawn. C~'.,.. 'W'.u..kl,. . . /~t. CHARACTER-- Factors Determining. GROUPS MEN IN 27 . DIFF~RENT CLA~S~S t • , • ...,;,.""'" ~J$ Prof. Brown Classifies Them According to Inheritance, Environment and Response; VALUES HEREDITY MOST liologiat Emphasizes the Importance of Good "Blood" or Cap?city in Choice for Marriage. ACCORDING to a sc.heme of classification drawn up by Herbert Eugene Walter, Associate Professor of Biology at Brown University, there are twenty-seven kinds ot men. By applying this classification to ourelves, Professor Walter states, we may honestly decld" which of the twentyl! even varieties we represent, for It may be possible, he asserts, within limits, to change ourselves If desirable Into different sorts of men. " Better yet," Professor Walter remarks, " we might try to classify our neighbor, whose faults, if not his virtues, are usually more apparent than our own. It Is always an engaging mental exercise to size up other people, since suc· cess In life depends largely upon correct judgments concerning those with whom we have to deal. In order to do this fairly, we must discover what deter· mines the sort of person our neighbor Is and wherein he or she differs from twenty-six other kinds of people. There are three contributing factors that go to make up any man-or woman-and no one of the three can possibly be omitted. " The first Is environment or the surroundings In which a person Is brought up. It represents the opportunity or chance In life which one has. The second Is natural capacity which Is Inherited from one's forebears. 'l'hls Is hered· lty or endowment. The third factor Is the response which Is made with a given Inheritance, whatever it may be, within one's parpcuiar surroundings. Envir· onment is the stage setting, Inheritance the actor and the response what the actor performs upon the stage. The play Involves all three. Environment Is what a man has; Inheritance Is what he Is, and response Is what he does. It takes all three of these things to make a neighbor or any one else. "Furthermore, Inheritance Is decided beforehand for every man. No one can choose his parents or determine the inborn capacity with which they endow him. It is too late to do that when one arrives on the scene. If a man draws a blank in his biological inheritance he Is simply out of luck, for he cannot cha.n.ge It or draw again. No Cauo~ for Shame. "This is why there Is no real reason for any one to be either proud or ashamed of his · blooci ' or his ancestry, whatever It may bE:. He had had no hand In determining \t. One may, however, properly feel pride or shame for the environment In which he remaTns or ror the re~ponse that he makes with whatever ability he has to that environment, since both of these factors are to a degree within his control. When he marries he may also feel pride or shame in the mate whom he chooses to be the fellow-determiner of the natural capacity which he wills to his children, because It Is within his control thus to enrich or cheapen the blood that he baR to pass on to the next generation. "To reduce the matter to the simplest terms, the three fateful factors that determine a man-namely, environment, heredity and response-may each occur in at least three varying grades, lntllcateu roughly as good, medium and poor. By combining these factors we arrive at twenty-seven kinds of men. For example, the Inheritance that a man Is born with ma)' be good, . me· dium or poor. Likewise the environment In which he finds himself and the response which he makes under the circumstances may be also good, medium or poor. In the list below are given the twenty-seven pos"lble combinations re· suiting from this simple arrangement: Inheritance. Environment. H.esponse. 1 Good ( ~ood Good t Good Good Medium 3 Good Good Poor 4 Good Merlium Good 5 Good ·MuUUm Medium 6 Good Medium Poor 7 Good Poor Uoorl 8 Good 'Poor Medium 9 G- Poor ~M 10 )rlf'dlum Good Good 11 ~1edtum noorl 'Medium 12 Medium <;oorl Poor 1:~ J\.ledlum Medium Good 14 Medinm Medium Medium 15 Medium Medium Poor 16 Medium Poor Good J7 Madlu•n Pool' Medium lR ,\[edlum Poor Poor 1 ~ Poor Good Good 20 Poor Good Medium 21 root Good Poor 2~ Poor Mcdiutn C1ood 23 Poor Medium Medium 24 f'oot· Medium Poor 25 Po01· Puor Good :!H Poo1 Poor Medium 27 f'eor Poor Poor " \Ve a.re now ready to classify ottr neighbor. Which of the twenty-se' en possible types does h<' represent end what hope is there of transforming him into a better man? Take the ca•e of 11 man like numbe1· fourteen in the li~t who iH ·medium' in nll of the three detet·mining particulars. How can he ~h!ft his position in the scale of life and become a different man? A 1\ledlum Example. " In the first place, he cannot change his heredity, for, unlil<e the heir who Inherits material property, he tan neither lose nor add to his heritage of innate capacity any more than a rabbit can lose or add to what makes It a rabbit and become a bird or some other animal. A man born medium in capacity must remain so. He .can mod if.: the environment which holds him In 1ls Influential embrace and he can also change his response to that environ· ment, either through education, experience and effort, or by the neglect of these means, so that the result will be a dlffere·nl kind of man. their ilolotrca tnnentan<'e or blood. A man may marry a fortune and lose tt, hut he cannot lose his mother-lro-law and all she means lo the blood of his <'hildren. It Is tar better. Indeed, to' marry good bloorl than good environ·: ment, because natural capacity usually 1 lea<ls, sooner or later, to an elfoi<ltlve rE'sponse which Is llkel;y In the end to insure a desirable environment. · The self-mado man who feels rommutdable pride In hi~ handlwork Is one who. ha~ risen In the t·an-s of the twenty-seven kind" of men, b\lt no one, even In a <)emocracy, can go all the way from the bottom of the ladder to the top tn ot;te lifetime. That accomplishment ta.kes genemtlons of tlnw antl a julildvus Mlecllon or one's grandparenta." • ·• Moreover, It is plain that In :-elect· lng a mate for our neighbor, which iR ahva,·R leRs complicated than t~electing a mate for one's self, No. 9 In the list, that Is, a person with good lnherltanc<>, l..·::?or environntent and ,DOOl' re:-;pon8e, -·Uld be a better risk for him th~n No. 19, for instance, wlilcll aenotcs a person with poor Inheritance, good environment and good response, not only because there would he mo1·e hopr• of I improvement during the lifetime of th•· I prospective partner, but Rlso b<>cau~e th<> possible chilciren of such a union would start lifo! with better • blood ' or capadty, and that I~ "' pri~f'le~s thin;:;. " Too frequently what pass68 for a · good match ' In socictl- ref•'rR ROlely. to ~nvlronment and m:tt.Prial po~,..,~~ions of th parties concerned rather thun to I b. CHARACTER-- Tests of. What is his code of honor? ("sense of obligation to some standard other than one's own wh1m or pleasure or advantage .•• a feeling of loyalty towards others regardless of cond~t1ons or consequences") . Is h1s word of honor inv1olate? Would he desert a fr1end? betray a trust? Do "the generous and heroic predom1nate over the mean and selfish in his life?" What is the dominant note that rouses music (sent1ment) in his heart? What is the spark that f1res h1m to enthusiasm? How does he bear suspense? V- ~ ... '~ c How does he carry prosperity? How does he meet d1saster? What lS t.he result upon him of unbearable strain? What is hlS ideal of happiness? What does he most fear? hate? loathe? admire? love? ~ ... rr~ - t. ~;..,e; ~)~~~o-r~,~· Novelty-- Adventure. Knowledge-- Eaucation. Position-- Achievement. Supremacy-- Power. Love-- Sex, Family. Luxury-- Wealth. Serenity-- Religion. CHARACTER - Shows in Emergencies • .•• "in those crises in which reason is most fettered, character is most potent . " Moulton, 57 . .. It~ f; .. I . CHARACTER-- Spurs to Effort . "Man needs obr.;tacles to bA overcome,to be great either in courage or magnanimity; he needs the sense of injuHtice, of wrong , of unmerited contempt; he needs the 'Nrath against these things without which man becomes paHsive like non-carnivorous animals . " (Harold MacGrath, The ~rey Cloak . ) ~ cienc and ~ligiqn I ( 1 v 'j edge. lie may say that beauty is cicntifically indefinable, p~ - ¥" but he does not say that it is therefore unknowable. If he rr IllS has been called an irreligious age. And yet of all did he would deny life itself. Darwin rec-ognized the dis the addres~e~ at the recent great meeting in ~ ew York tinction when he wrote: of the American Association for the Ad1·ancement of "~Iy mind seem to halT become a kind of machine for Science the one that commanded the widest public attention grinding general laws out of large collections of fact . . .. and stirred most comment was an address on religion. If I had to li1·c my life again, 1 would haYc made a rule to It was not a scientist who caused this intellectual uproar read some poetry and listen to some mu ·ic at least once e1·ery but-the distinction is Yalid-an historieal sociologist, a pro- week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied fessor at Smith College, Dr. Harry Elmer Barnes. If a would thus ha1·c been kept aeti1·c through us . The loss of notion of God is needed, he said, "it i~ of littl' 1·aluc to in- these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibl~· be inculeatc a 1•iew of God so hopelessly out of date a~ that which j urious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral was slowly and painfully e1·oln·d hy the semi-barbarous character, by enfct>bling the emotional part of our nature." Hebrew peoples in tl1c clays when a rudimentary type of, Science can sen·e cxprriencc by pointing out the blind geocentric and anthropomorphie outlook reigned supreme alley of life. It can sa1·e, and has sand, men from fear by and unchallenged .. .. . Christian solt:mnity mu~t b · replaced helping them to di tinguish between religion and superstition. by the frank joy of life .... Sin is scientifically indefinable It can release, and has rclea~cd, men from nanowncss and and unknowable .... The psychoanalysts have already shown bigotry by destroying religious conceptions that ha1·e trnmtbat the 'sense of sin' is but a psychophysical attribute of mclcd their minds. Though science cannot be a substitu te adolescent sentimental del'elopment." for religion it can be a conccti1·c of religiou · misconceptions, In spite of himself, Dr. Harry Elmer Barn s is a thcolo- and create a more challenging conception in their place. gian. Religion is no more theology than the ·tars arc astron-omy, or flowers are botany, or people arc anthropology and Religion is not primarily a conception of I ifc; it is rather ociology. What the Hebrew people and their literature a way of living. It sets a goal and it supplies power. Ex 'were concerned with was not any religious conception but pressed in another way, it is a relationship of life to sonH' religious life. \' hat Dr. Barnes want· are new religious thing or someone outside itself. That is why Jesus spoktconceptions. of God as Father-not as a religious conception hut as a One man sees a bird and he writes a book on ornithology. relationship. Jesus was an iconoclast-as ieonoclastic as Another man sees a bird and he writes "Hark, hark, the lark science. He would do away with eiTrything that interfered at heaven's gate sings." The Dr. Barnes type of man may with that life, that relationship. Hate yom father and prove that there can be no gate of hcaYen; but the lark of the mother, sell all thnt you haYc, han' no care for the morrow, poet still sings at heaven's gate for l'\Try one who has cars let tbt• dead bury their dead-no expression was too strong to hear it. \Vhat Dr. Barnes and others eYcn more expe- for his purpose. Ilc was not a theologian; he was only in rienccd than he take to be religious conceptions based lcidcntally a teacher. He was first of all a leader. Th • gist on an antique idea of the uni1·crse arc poetic images employed of all he said wa~. "Come ad1·enture with me." So far ;1~ to express or suggest experiences that in other clays or by the churches fall short it i~ in the lack of Je~u~'s spirit of \ other people might be expre,sed or suggested by other poetic abandon. They offer entertainment when they might better images. At one period the Hebrew people were a pastoral offn the challenge "Come. we want your best." There i-, people. \Vhat more natural than that a poet should write many a man outside any ehurch, indifferent to c1cry creed. "The Lord is my Shepherd" or "The range of the mountains who is giving of his best to something bigger than himself in is his pasture." or (accustomed as herdsmen arc to watch the which he has faith-it may be to a boys' club or some public sky) "Canst thou bind the sweet influences of Cimah (the service-who would laugh if you called him religious. That Pleiades), or loose the bands of Ccsil (Orion)?" is because the churches l1a1e so largely confused religion with Dr. Barne is right, of course, in saying that our religious theology or with some code. Theologies change; codes conceptions should accord with our knowledge. Theologians change; but thee<; ence of religion, which is a kind of life. have taken poetic expressions of experience and built them remains the same. into dogmas and creeds and rituals and even codes of con 'Vhether a scientifie gathering is the place for a theological duct. And when they do that it is wholesome for some one discussion we leaYc to the scientists to d cidc. Dr. Osborn, to come alcng with a geologist's hammer and smash off the the retiring President of the A.A.A.S. thinks it is not. crust of theology, for only then will the experience of life Others think it is. ~lore and more it is becoming difficult beneath the crust be reYealed. Cone pts grow out of life. not to ereate intell ·ctual compartments-to wall off science from life out of concepts. ~Iusie comes fir~t. then the harmonic philosophy or t'ither from conceptions of religion. It is no and contrapuntal theories of musie. 'Vhcn rules of harmony longer as easy as it was to hold one set of ideas for six days and counterpoint dominate, the art of music languishes. It of the week. ancl another set for the sen·nth. Confused as is well then to haYC musical iconoclasts arrin• to knock off he seems to ha1e been in some of his thoughts, we are glad the shackles. But the old music out of which those rules that Dr. Barnes !>poke out. were formed is still b autifnl and Yalid; it is ~till music. The true scientist does not confuse the definition with the ry/' _,J::' , ~ -- thing defined. lie docs not deny beauty because science has ~~ ~ never defined it. Nor docs he confuse definition with knowl- ( }~ CHARACTER. "Foundations of habits (which means character) are laid in homes. • • • Good, honest, hard-headed character is a function of the home. If the proper seed is sown there and properly nourished for a few years, it will not be easy for that plant to be uprooted?. • • • We start with suppositions in judging character, intelligence, Eersonality. We must, of course •.•. Character seems to be an essence, a spirit, a core, a stuff, that defies analysis •... A limited repertoire of habits, an unlimited amount of emotion, and an enormous capacity to learn •• By the time one is old enough to vote-- whether it has learned what the ballot means or not-- it belongs to mother's church and father's party, and weare the clothes, thinks the thoughts, and swears by the flag the family and the community have wished on it. In short, its 'character' may be nil, its reputation fine." (Dorsey, Why We Behave ••• ) "Any attempt to explain or to describe man by a set of rules or by a special formula, or as cast in a given mold, is predestined to failure. Man is a something happening all the time, a going concern; he makes hie rules, revises his formulae, and recasts his mold in the act of being and while going. It is in man's nature that he does not stay put. Human behavior is individual behavior; • • • Instinctive behavior is insect behavior at its highest; human behavior, modifiable behavior at its highest. • • . We are born with certain instinoti ve aoti vi ties and emotional cr.paci ties • • • What seem clear-cut instinctive actions are learned or habit reactions based or built on some innate emotional response or on attack and defense reactions as old as life itself. And any attempt to describe human behavior in terms of such instincts is to try to catch birds by salting their tails • • • Man's chief impulse at each moment of hie existence is for life; self-preservation. At certain moments food-hunger dominates the self-preservation impulse, at other momenta sex-hunger dominates. But because of hie capacity to supplement his motor mechanism with tools, weapons and appliances, he was able to give his biologic impulses ever-changing outlets •.•• Man'e inheritance is all right and is his only inherently valuable asset. It is human behavior-- individual, communal, national--- that can be changed. • .• Man can learn. 11 (Ibid.) · PRINCIPLES. lp ------ Principle.-- A rule consciously and resolutely adopted as a guide to action when unqualified; a determined rule of right action, or habitual devotion to right as right; as, the principles of morality; a man of principle. (St. Diet.) "Since the generality of persons act from impulse, much more than from principle, men are neither eo good nor so bad as we are apt to think them. (A.W. and J.C.Hare.) Thou that uplifteet me. The bravest and noblest impulses of humanity. CHARACTER- Singleness of' Purpose- Dignity of' • .. • "The dignity that is always given to a character by a grand passion, whether for a cause, a woman, or an idea - the unification of' a whole life in a single aim, by which the separate strings of a man's nature are , as it were, tuned into harmony . 11 Moulton , l89 . PERSONALITY . The attributes, taken collectively, that make up the character and nature of an individual; that which distinguishes and characterizes a person. (St. Diet.) See CHARM. I~ PERSONAL APPEARANCE. Outward seeming or ~spect. AIR. The peculiar or characteristic appearance, mien, or manner of a person or thing. Syn.- Appearance, bearing; behavior, carriage, demeanor, expression, fC~.shion, loo.k, manner, mien. port, sort, style. way. Air is that combination of qualities which makes the entire impresaion we receive in a person's presence; as, we say, he has the air of.a scholar. or the air of a villain. Mien is closely synonymous with air, but less often used in a bad sense. We say a rakish air rather than a rakish mien. Mien may be used to express some prevailing feeling; as, "an indignant !Qi~.'· - Bearing is rather a lofty word; as, he has a noble bearing; Port is practically identical in meaning with bearing, but is more exclusively a literary word. Carriage, too, is generally used in a good sense; as, the lady has a good carr1age. Appearance refers more to t~e dress and other externals. We might say of a travel-soiled pedestrian, he has the appearance of a tramp, but the air of a gentleman. Expression and look especially refer to the ~ace. Expressio!}- is oftenest applled-ro-that which is habitual; as. he has a pleasant expression of countenance; look may be momentary (but, he had the . look of an adventurer; I d1d not like his looks). Demeanor goes beyond apkearance, including conduct, behavior; as, a modest demeanor. Manner and style are, in large part at least, acquired. Address is the manner of a ~erson in speaking or addressing. (See th1s heading.) Behavior is the manner of conducting oneself, whether good or bad, especially in the externals of life. Behavior is our action in the presence of others; conduct includes also that which is known only to ourselves and our Maker. Carriage expresses simply the manner of llolding the body, especially in sitting or walking. Bearing refers to the bodily expression of feeling or disposition; as, a hauehty bearing, a noble bearing. Demeanor is the oodily expression, not only of feelings, but of moral states; as, a devout demeanor. Breeding, unless with some adverse limitation, denotes that manner and conduct which result from ~ood birth and training. Deportment is behavior as. related to a set of rules. A person's manner m~y be that of ·a moment, o~ toward a single person; his manners are his habitual style of behavior to~ard or before others, especially in matters of etiquette and politeness; as, good manners are always pleasing. PHYSIQUE- Male. ll.jti,.._ ~ ¢-~-~ ~~:/ ~- • s PHYSIQUE- Female. CHILDREN . Swarming with weedy children, a rank but weakly growth. J I BEAUTY. Perfection of form, with softness of outline and delicacy of mold. There must also be harmony ~nd un1ty, and in human beings spiritual loveliness. to constitute an object or a person really beautiful. Pretty expresses to a far ~ess degree th~t which is ~leasing to refined tastes in objects comparatJ.vely small, slight and dainty. Fair denotes what is bright, smooth, clear and w1thout blem1~ The word applies solely to what is superf1cial. 7 Comely denotes an aspect that is smooth, gen1al, and wholesome, w1th a certain 1·u1ness of contour and pleasing symmetry, though fa~llng short of the beautiful. Pleasantand pleasing both refer to giv1ng pleasure, but w1th a difference in usage. A pleasant race 1s that of one who appears to fee~ pleasure and to be desirous to g ive pleasure. A pleasing face is one tha t pleases us by simple contour and expression. For Attractive. Agreeable, Amiable, Engaging, Winsome, Charming, Lovely. etc .• see under DISPOSITION. STRENGTH. Muscular, br~wny, Athletic. sinewy, well-knit, wiry (thin but tough and Robust, lusty, vi~orous, able-bodied, Stalwart, burly, powerful. Hardy. Enduring. endur1ng). rugged, sturdy. ... FEEBLENESS. Weak, weakly, feeble, frail,delicate. Soft, effem1nate, languid, alack, flaccid, flabby. Slender, slight. Nervous. unnerved, unstrung, irresolute. Broken, lame. Withered, palsied, tottery. drooping, rickety, infirm, wasted, decrepit, sickly, deb1litated, trembling • Jo DEFORHITY. NIMBLE. Light and quick in motion or action; showing easy qulckness; ag1le; dexterous; (2) intellectually alert or acute; quick of apprehension. Nimble refers to ~ightness, freedom. and quickness of motion within a somewhat narrow range, with readiness to turn suddenly to any point. Swift applies commonly to more sustained motion over greater distances. Agile: able to move or act qu1ckly, physically or mentally; active; n1mble; brisk. Jhen used of the mind often bnplying trickiness; as. an agile controversial1st. Antonyms: clwrsy, dilatory, dull, heavy. inactive. inert, slow. s~ug ish. unready. II 12 DEXTERITY. Adroitness carries more of the idea of eluding, parrying, or checking some hostile movement, or taking advantage of another in controversy; dexterity conveys the idea of doing, accomplishing something readily and well, without reference to any action of others Aptitude is a natural readiness, which by practice may be developed into dexterity. Skill is more exact to line, rule. and method than dexteritl· Dexteritv can not be communicated, and oftentimes can not even be explained by its possessor; skill to a very great extent can be imparted. Handy; having skill with the hands,or otherwise; apt at doing things. Clever; ready and adroit with hand or brain; capable. Elasticity. "But the imp of' a fellow yielded and recovered himself' in quick succession like a spring . " About. I GRACE. That char~cteristic or quality which renders the carriage, movement, form, manner, etc., elegant, appropr1ate, or charming. Graceful commonly sugeests motion; it applies to the perfection of motion, especially of the lighter motions, which convey no suggestion of stress or strain, and are in harmonious curves. AWKWARDNESS. Ungraceful in bearing or person; ungainly; uncouth. Clumsy; bungling; inefficient. Embarrassing or embarrassed. Awkward primarily refers to action, clums;y to condition. The q_ll;lmSY, man is almost of necessity awkward, but the awkward man may not naturally be clumsy. The finest untrained colt /S is awkward; a horse that is clumsy in build can never be trained out of awkwardness. Clums;y is applied to movements that seem as unsuitable as those of benumbed and stiffened limbs: maladroit. Bungling.: performing in an awkward and blundering manner. Gawk;y; staring or otherwise behaving awkwardly and stupidly. Uncouth: marked by awkwardness or oddity; especially. appearing thus marked because of unfamiliarity; outlandish. Ungalnlz; lacking grace or ease. NEATNESS . That which is clean is simply free from soil or defilement ·of any kind; things are orderly when in due relation to other things, Tidy denotes that which conforms to propriety in general. Neat refers to that which is clean and tidy, with nothing superfluous, condpicuous, or showy. Nice is stronger than neat, implying value and beauty. Spruce is appl1ed to the show and affectation of neatness with a touch of smartness, and is always a term of mild contempt. Trim denotes a certain shapely and elegant firmness, often with suppleness and grace. Prim applies to a preciae. formal, affected nicety. Dapper is spruce with the suggestion of smallness and slightness. Natty, a dim1nut1ve of neat, sug~ests minute elegance, with a tendency toward the exquisite. 16" SLOVENLINESS. Carelessness and disorder of dress, or negligence of cleanliness. Dirty, dowdy, untidy. /8 HEAD- Male . /9 HEAD- Female . FACE, FEATURES - Male. For this war has done something to the faces of the men who have borne the brunt of it. An entirely new physiognomy has come into being-one that might be called the war face. All persons who have been in Europe since the fighting began must have noticed it. The expression of the features is unmistakable. It is not precisely a sternness or harshness or melancholy or anything of that sort, but a peculiar rigidity of the features and somber look in the eyes when the face is in repose. It is set like a seal upon those who have gazed upon terrific things and is rather like a mask drawn over the face, as if the mind back of it had learned how to hide its feelings behind a bomb-proof camouflage. But Gaston whipped this off and smiled on catching sight of me, and you would have thought from his buoyant and grateful manner that the President himself had come down to meet him. He was better looking than his pictures, a little above medium size, strongly built, with a square bony frame, good, straight, clean-cut features, lean cheeks and a pair of steady dark-blue eyes. Most of the time they were twinkling and brimming with high spirits, but let him grow thoughtful and contemplative for a moment and that war mask slipped on again unconsciously. () 21 FACE, FEATURES - Female • t a... J ; a ·G- •*' '..t,.,i. d~ 17 =• FOREHEAD . ''i/v.-~ ~ ~ ~~ ~~~ Cll¥) EYEBROWS. EYELASHES. NOSE • • 2J MOUTH. ~-~ (JitM~). TEETH. CHIN. 0 CHEEKS . .. Jl EARS . HAIR. ~-l.u.kt, BEARD . SKIN. "~~/ ~ ~. lif.,4. ~~, 4 Ill-~~.£..... _/ __ _ ... __ /tu:)..Ju,..J..P. ~ ~~~ .,.ui!.J;-~, ~-~~ c£~,"' ~ ,--,-- I MOLES, VTRINKLES. NECK . u) BODY, CONTOUR, PROPORTIONS- Male . BODY, CONTOUR, PROPORTIONS- Female. a LANK. Lean and sinewy men. These wiry men, thin but tough and enduring as a pack of hounds. A stringy individual in rusty garb. A thin, sharp-featured man. Spindling. Narrow-chested and flat-hipped. Gaunt. Poor. Spindling. Spare. Meager. Shriveled. Withered. Bony. Barebones. Raw-boned. Big protruding joints. Big wrists and Xnuckle-joints. Hatchet-faced. Lantern-jawed. A thin visage. Gaunt, pinched and grim. Emaciated. Walking skeleton. Mere skin and bones. Pinched .face. Thin and wan. Famished-looking. Starveling. Wasted figure. A cadaverous creature who looked as if a puff of wind would knock him down. Sallow. Pasty-faced. Tallow-faced. A sickly yellow face. SLENDER-SYMMETRICA~. Her slender 1 well-rounded figure. ATHLETIC BUILD. Symmetrical. Well formed. Well braced. Able-bodied. Muscular. Brawny. Burly. Powerful. Stalwart. Large and strong in frame. Of sturdy build and disposition. Lusty. Sturdy. Rugged. Vigorous. Abounding health. Lithe. Supple. Limber. Elastic. Lissom. Pliant. Willowy. Agile. Active. Nimble. Supple. Prompt. Quick. Speedy. Swift. Alert. Brisk. Quick. Lively. Mobile. Restless. Sprightly. Spry. Wide-awake. Dexterous. Clever. Handy. Skilful. Adroit. Apt. Expert. Facile. CHEST . BREASTS - Female . WAIST- Female . HIPS . ARMS. HANDS . LEGS . FEET . DRESS.-- Male. • I DRESS.-- Female. WOMAN-- Passon for Ado~mment. No man, perhaps, could have been chosen for the position ceditor of The Ladies• Home Journal] who had a less intimate knowledge of women. Bok had no sister, no women confidantes; he had lived with and for his mother. She was the only woman he really knew or who really knew him. His boyhood days had been too full of poverty and struggle to permit him to mingle with the opposite sex. And it is a curious fact that Edward Bok 1s instinctive attitude toward women was that of avoidance. He did not dislike women, but it could not be said that he liked them. They had never interested him. Of women, therefore, he knew little; of their needs less. Nor had he the slightest desire, even as an editor, to know them better, or to seek to understand them. Even at that age, he knew that, as a man, he could not, no matter what effort he might make, and he let it go at that. . .. A home was something Edward Bok did understand. He had always lived in one; had struggled to keep it together, and he knew every inch of the hard road that makes for domestic permanence amid adverse financial conditions. And at the home he aimed rather than at the woman in it. (The Americanization of Edward Bok, p.l68.) The strangling hold which the Paris couturiers had secured on the American woman in their absolute dictation as to her fashions in dress, had interested Edward Bok. for some time. As he studied the question, he was constantl:y amazed at the audacity with which these French dressmakers and milliners, often themselves of little taste and scant morals, cracked the whip, and the docility with which the American woruan blindly and unintelligently danced to their measure. . • • The Journal engaged the best-informed woman in Paris frankly to lay open the situation to the American women; she proved that the designs sent over by the so-called Paris arbiters of fashion were never worn by the Frenchwoman of birth and good taste; that they were especially designed and specifically intended for 11the bizarre American trade, 11 as one polite Frenchman called it; and that the only women in Paris who wore these grotesque and often immoderate styles were of the demimonde. Sarah Bernhardt was visiting the United States at the time, and Bok induced the great actress to verify the statements printed. She went farther and expressed amazement at the readiness with which the American woman had been duped; and indicated her horror on seeing Ametican women of refined sensibilities and position dressed in the gowns of the declasse street-women of Paris. • •• Bok called upon the American woman to come out from under the yoke of the French couturiers, show her patriotism, and encourage American design. But it was of no use .... One of his most intelligent woman-friends finally swmned up the situation for him: "You can rail against the Paris domination all you like; you can expose it for the fraud that it is, and we know that it is; but it is all to no purpose, take my word. When it comes to the question of her personal adornment, a woman employs no reason; she knows no logic. She knows that the adormffient of her body is all that she has to match the other woman and outdo her, and to attract the male, and nothing that you can say will influence her a particle. I know this all seems incomprehensible to you as a man, but that is the feminine nature. You are trying to fight something that is . unfi: ghtable." -2- "Kas the American woman no instinct of patriotism, then?" asked Bok. "Not the least," was the answer, "when, it comes to her adornment. What Paris says, she will do, blindly and unintelligently if you will, but she will do it. She ~ill sacrifice her patriotism; she will even justify a possible disregard of the decencies. Look at the present Parisian styles. They are absolutely indecent. Wonten know it, but they follow them just the same, and they will. It is all very unpleasant to say this, but it is the truth and you will find it out. Your effort, fine as it is, will bear no fruit." Wherever Bok went, women upon whose judgment he felt he could rely, told him, in effect, the same thing. They were all regretful, in some cases ashamed of their sex, universally apologetic; but one and all o.eclared that such is "the feminine nature," and Bok would only have his trouble for nothing. And so it proved. ··~ (Same,327-332.) During his investigations into women's fashions, he had unearthed the origin of the fashionable aigrette, the most desired of all the feathered possessions of won~nkind. He had been told of the cruel torture of the mother-heron, who produced the beautiful aigrette only in her period of maternity and who was cruelly slaughtered, usually left to die slo ·ly rather than killed, leaving her whole nest of baby-birds to starve while they awaited the return of the mother-bird. . • • tHe fought the fashion~ After four months of his campaign, he learned from the inside of the importing-houses which dealt in the largest stocks of aigrettes in the United States that the demand for the feather had more than quadrupled! Bok was dumbfounded! ..• 11 It will be hard for you to believe, 11 said on.e of his most trusted woman-friends. "I grant your arguments: there is no gainsaying them. But you are fighting the same thing again that you do not understand: the feminine nature that craves outer adornment will secure it at any cost, even at the cost of suffering." "Yes, 11 argued Bok. "But if there is one thing above everything else that we believe a woman feels and understands, it is the mother-instinct. Do you mean to tell me that it means nothing to her that these birds are .kil ~ed in their period of motherhood, and that a whole nest of starving baby-birds is the price of every aigrette?" "I won't say that this does not weigh with a woman. It does, naturally. But when it comes to her possession of an ornament of beauty, as beautiful as the aigrette, it weighs with her, but it doesn't tip the scale against her ossession of it. I am sorry to have to say this to you, but it is a fact. A oman will regret that the mother-bird must be tortured and her babies starve, but she will have the aigrette. She simply trains herself to forget the origin." [BOk aroused the men. The butchery was stopped by legislationJ ~ok had won his fight, it is true, but he derived little satisfaction from the character of his vic~~r~rJN~1i ideal of womanhood had received a severe jolt. He was ~ware ttat his mother's words, hen he ••• n .. a..P~~;;.f;Q.. his editorial posit io.a~113Jt~~:11pOming terribly true im ... •d·"''" ·sN1991M .M .M •••n•o•s 'SNIJV31S :>1 'I ~N•otu•d 'liJVHd3)1 3:>YIJOH "I am sorry you are goingNOI±VI:::>O~SW to take this position. It will cost you the high·i~ea yOu naVe a~ways held of your mother's sex. n • • Such exper- 3~V~ ONV' HSI.::I iences as these-- and .. unfortunately1 they were ]'J'o'IH:::>VIVdd~ only two of several-were doubtless in his minu wnen, upon liis retirement, the newspapers clamored for his opinions of women. "No, thank you," he said to one and all, 11not a word." He never did give his reasons1 He never Wl~l. STOCK. The line of descent. Race, family. ' HEALTH. DISPOSITION. Mental tendency and 1nclination, whether natural or acquired; especially, temper or temperament; character1stic mood cr spirit; habitual bent or propens1ty. Ap.J,!lied ooth to the primary and natural tendenc1es of temper and temperament, a nd 1.0 the secondary or acquired tendenc1es emoraced under habits. DISPOSITION What Is the Greatest Domestic Virtue? I Dorothy Dix I I Says Its Being Pleasant to Live With Not Even a Vamp-Proof Husband or a Beau· tiful Wife Spells l~arried Bliss- But the Hus· band or Wife Who Makes Life One Grand, Sweet Song, Is the One Pleaslltflt to Live With A YOUNG husband, speaking of his bride, said to his mother: "She l.s so pleasant to live with." Whereat the mother breathed a prayer of thanksgiving, for she knew that all was well with her beloved son. The gods had vouchsafed him the greatest earthly blessing, the kind of a wife whose price is, indeed, aboye rubies. For, when all is said, the greatest of all domestic virtues iR to be pleasant to live with. It is the disposition, not the morals, nor the looks, nor the brains, of the high contracting parties that make marriage a success or a fai!ur<', and determine whether •the participants are to be happy or miserable. Which is the reason why many a saint with a grouchy temperament and a two-edged tongue , gets hauled into the divorce court, and why many II an easy-going sinner leaves behind an inconsolable widow or widower. ---- li Jt is curious but trUE', that things that count so much hcforo marriage matter very li tllc a ftcr marriage, Beforr marriage 've put great stress on personal pulchritude, on mental brilliance, on suave : and charming manners. We are allured bY a beautiful face. We arc fascinated by n. witty and entertaining conven<al! onalist. We are charmed by thos<' who have graciousnPss and poise, hut after marria.ge we grow tired of looking at even a living plcturP, imd we Aoon cease to see beauty in it if that is all there is to <t person. Nobody can perpetually scintillatC' !n the family circle and they would bore us to death if they did. Nor is there any place for the gran~ manner in everyday home ]if(', fJr all the graciousne~l'! and aC'co~plishments and talents p;o Into the discard, and that thing that is of vital Importance is just the disposition of thP one with whom we have to live day in and day out, in good weather or bad, in prosperity or adversity, in sickness or in health. Of courst>, viewing- the matter from an ethical Rtandpoint, a wife is glad that her husband l!< " man of prohity, whose word ls as good as h is bond, and that he i!'; spoken of as "Honest John Jones.'' But the knowledge that her husband is incorn;:;:Jtibly honest does not ma.ke it any easier for :!\frs. John Jones to get money out of him if hP is a tightwad, nor docs it take the stin;; and humiliation out of her having to panhandle him for carfare nor keep her from hating him on the first of every month when s e tremblinp;!y prrRentR him with the monthly bills and goes through the ecenes that ensue. The thing that would make for her happiness would b!' for him to be pleasant to live with, for him to he fair and generous about mon<'y and for him to give her what he could afford without haggling over it. It Is a gratification to a woman to know that her husband is n« vhllander, that vamps would vamp him in vain, and that he would rather have a toothless hag of a stenographer who could spell than the peachiest flapper who was not on speaking terms with the dictionary. But faith1'ulnPsa Is of Rmall avail in making a wife happy it bet husband apparently rt'gards her as nothin~ more than a piece of UI!Pful household furniture; If he nev!'r shows her any tenderness or 4ffect!on or gives any sign that he still cares for her. The thing that would make her go down on her kneefl, and thank Go<l. for hn,in~ given her her heart's desire in a hu1!band would be for him to be plea:<ant to live with, for him to keep up the love-like attentions of their courting days; for him to still give her kisses that had a thrill to them, !nstPad of having the !n:mlting, clammy flap of a cold bu<'kwheat cake; !nr him to t<'ll hPr that Fhe grew more beautiful to him and rl~>~trPr as thl' years went by, and that his lucky day II was the day he got her for a. wire. ------ A woman rejoices in her hu&band's success in bu11lnei!IB. She liS proud to know that he Is ret'lpected In the community, but she can be utterly miserable if he has a surly and a grouchy disposition; if he never speaks at home except to find fault, and If the famlly lives In terror of doing or saying something that will bdng on a maniacal burst of tflrnper. The hlli!band who makes life a grand, sweet song to hi!! wife Is the man who Is pleasant to live with; the man who is sunshine and strength In a home; who Is cheerful and goodnatured; who jollies his wife and pets his children, and at the very sound of whose key In the door everybody brightens up and begins to smile. And pre sely the same thing Is true of wives as of husbands. Tht g-ood wife Is not necessatily the best woman, or the best cook, or the best housekeE-per, or the best manager, or even the woman who loves her husban<l best. Many a woman who would gladly die for her husband nags him so that he would be w1lllng to die to get rid of her. Many a woman who saves every cent of her husband's money Is equally economical of her consideration for him. Many a woman who possesses all ot the virtues has none of the amenities of II fe. The perff'd wife Is the woman who Is pleasant to live with, no matter whether 11he can cook, or has the bargain complex, or Is a highbrow or a lowbrow. She is the woman who II! cheerful and good natured; who is reasonable; who Is a good sport; who iR appreciative and contented, and who can :say a thing once and let it go at that. That Is why being pleasant to Jive with Is tht> great domestic virtue. DOROTHY DTX. Co;-Jyrlght, 1 n24, by Public Ledger Company. 'VNnO~'VO H.L~ON 'A.LIO NOSA~8 .:10 NMO.L .. liN¥Y3.LS ' )I '1 >4M3,;:) 'A:EnNO::l '.L 'M NYHWIYH~ I .1Y't'Hd3}1 3:)'9'MOH N3WH301V .:10 OHVOS swvn,IM 'd ·o t!OAV.-. AMIABILITY. Amiable: possess1ng ~he ~greeable moral or soc1al qualities that please and make f'rlends; fr1endly or pleasinb in disposit1on; kind-hedrted; gracious; uenial. Combines the senses of lovable or lovely and lov1ng. A d1s~os t~on to cheer, please, and make happy. Lovely is often applied to externals. An agreeable person is one who would readily win favor in any company. An attractive person is one who possesses vivacity, wit, good nature, or other pleasing qualities. A selfish man of the world may have the art to be agreeable; a handsome, brilliant, and witty person may be charming, while by no means amiable. The attractive, engaging. winning, and winsome add to amiability something of beauty, accomplishments, and grace. The benignant are calmly kind, as from a height and a distance. Kind, good-natured ~eople may be coarse and rude, and so fail to be agreeable or pleasing; the really amiable are likely to avoid such faults by their earnest desire to please. The good-natured have an easy disposition to get along comfortably with every one in all circumstances. Amiable is a stronger word, "characterized by that friendliness which awakens friendliness in turn." A sweet disposition is very sure to be amiable, the loving heart bringing out all that is lovable and lovely in character.. A considerate person carefully spares another all that would harm, grieve, or annoy. ANTO~YMS; abominable, churlish, cruel, disagreeable, hateful, ill-conditioned, ill-tempered, unumiable, unlovely. CHARM. 52b I I CHARM . FEMININE FASCINATION. A Charm That Probably Llea In Kindness and Selfleaaneae. A vivacious woman writer seeking the aecret ot feminine fascination, finds It 1\ the art or power some women have of charming others by putting them, aa e. bluff Britlsher phrased it, " on ripping good tenns with themselvea," Is not I :~~~~~r::~~~t~o:e:.~~~:~~= I the beat and enjoy the most? Do they I not, either by artifice or by Instinct, en-deavor to make tho people they cont&ct feel that they amount to somethln&", know something, have some excellence, attractiveness or interesting qualities, and thus put them on pleaaant terms with themselves? The persons who e.re least adept at thla or least Inclined to try It are the self-centred, self-Important people completely absorbed In their own affairs and not wise or well-bred enough to conceal the tact. They live In little worlds ot which they are the centres, and may be sa.ld In a certain sense to revolve about themselves. This is a characterlBtt~: brought up from lower f.orms of life from which we are ancestrally derived and only In part· outgrown. For most animA-ls thl' only concerns of the leut Importance are those which directly attect themselves. They an; ·egocentric. The things that touch them make up their world and they have no lntere~ts outalqe o( t)lat. More t)lan any other animal the dO&' can sink his personality 110 t.o speak, aubordlnate hlmselt and make his mMter'R Interests his own. Only infrequent Individuals of other species can or will dQ this. Hence doge as a rule are more companionable for 1 man than any oth!'r living creatures below him In lhe evolutionary acalc. Hut to return to human beings, Josephine waR the most beloved anu · charming woman In France because she took a genuine ancl kindly lnt4!r<;lst In the affairs ot all .with whom abe came In touch. She was outgolnc, Inclusive In her sympo.thlen ~ thul! counteracted antagonism created by Napoleon, who was self-c<'ntred io an extraordinary degree. Not to rnultlpl:v examples, does 1 not experience teaeh all obaervant pOOph' that In se\flessneRs llt>PI the secret of charm? Are not th<' lovable people those ·j whose love goes out spontaneously, or\ appears to? Is not ecocentrlcity, entire absorption In th.,meelves, a characterlsUo held in common by most of the people who ~ret on on"'s nervtos? Kind heart'!! are mot•e than coronets, said Tf>nnysnrt : and that fot•f!'otten poPt of our grandslrcs, Martin Tupper, found Jove· to be the charmer ch.,rmlng wb~ly v.·t>o was mlghtll't' than Ma.nnah's son. More attractive, therefore, than beatllY or the brilliancy and glitter of lntellectua.llty Is the drawing power at kindly coneldPratlon for others. Faa· clnatlon I• born of the heart, ~ot of the mind ; and whether Instinctive or acquired, would seem to be the art of enwrin&' into the live~ of otbera and putting thf'm, a.s the Englishman said, on rrood tf'rms with themselvcs.-Roches-ter Post Express. • 52b3 CHARM. "A 'pleasing, 1 'thrilling, 1 'absorbing• personality is one we like to touch. Men shake their hands. Women kiss them. When 1 ! instinctively like that person,• the instinct that is talking is an unanalyzed sexual or emotional slant based on early habits of love. A 'lovable' personality within the same sex is possible because sharp leanings toward the other sex were not formed at the time sex matured. Co-education is sanitary education. "We jump at our personality conclusions. We know he cannot be this and she cannot be that. What we really know is that some personalities appeal to us, others do not. We can rarely give the real reason for our spontaneous judgments. Personalities are rather more complex than apples or motor cars. 11The most •erect carriage' may be the greatest social scoundrel unhung. The 'intelligent brow• may be housed under a dunce's cap. The 'squarest chin' may be a weak sister and the most henpecked man in town. The 'firm mouth' may hide a flabby body and a soft head. "Some things do show through: elation, despondency, etc. But the rosiest cheeked apple may have a wormy heart." (Dorsey, Why We Behave ••• ) CHARM . What EYel'J' I D h D Js Goln~ to 1 :~!:w \ orot y ix -~E. ------------' .. -----------------------------~~--------------- The Riddle the Spinx H·as Brooded Over for Centuries Without Solving-Stress Your Femininity if You HaveN o Charm Over and over again girls ask me these questions: What is charm? What is the secret of the attraction that some women have for n1en? What Is the "come-hither" look in the eye that some women have that makes every man who beholds it get up and follow them? Why do some girls alway~ have hos t>< of beaux flocking about them, whlle other girl>< just as good looking, just as clever, just as good dancers, just as anxious to please, never have a date or a single sweetheart to bless themselves with? • And to till of these questions 1 have to answer, sadly and disconsolately, that I <lo not know. I have to give up the conundrum, which is. perhaps the riddle that the Sphinx, who is also n. woman, has brooded over through the centuries in her desert solitude, without ever being able to solve it. In Barrf()'s delightful play, "What Eve'ry Woman Knows," Maggie's brotherR, dl,.cusslng h<'r with the brutal frankness with which brothers approach the subject of a sister, ugrced that sho wasn't young, nor brilliant, and that she was homely, yet all the men were after hPr. l!'lnally one of the brothers said: "But she'~ got that damned charm." And that was that. When a woman has that damned charm she ean snap her fingers In the face of flappers and living picture, and marry as early and as often as she pleases as Is witnessed by the many fat, pll'-faced women we all know who have had two, and three, or more husbands a f) ieee, and who still have a waiting list in case anything untoward and fatal ehoulfl happen to the gentleman to whom they arc at present united in the holy bonds of•matrlmony. But what is this charm, what Is this rabbit's foot that some lucky women carry and others do not? To say that It i spersona! ity is to attempt to explain one mystery by another mystery, for we do not know in what personal magnetism consists, or by what power one individual draws us, while another repulses us. We all know ·l,hat it isn't beauty, because the best lookers among girl.! are selftonl tnt> most popular, and men who profess to worship beauty arc generally content to adore it from a safe distance, and show no disposltlon to marry it. It is notorious that beauties seldom make good matches. Nor does charm consl..st of Intelligence. Being a highbrow booms no woman's stock, socially or matrimonially, while a witty woman cuts her throat with her own tongue. To be a Rpellbinder Ia for a girl's fairy godmother to have wished a curse instead of a blessing upon her, for no woman !11 more anathema to men thfUI the human phon<>graph. Even dancing, chief of ac• comp!ishments in these jazzy days when it is o! more profit for a worna n t.o have her brains in her heels than In her head, is but a paslng attraction, while amiability and a sweet nature, woman's traditional one best bet, are like a sticking plaster, potent to hold a man after marriage, but of small value in luring him into it. Undoubtedly, charm In Its perfection Is a gift of the gods, hut happily, in these days, when nature proves a cruel stepmother who Is so mean and stingy that she does not give u~ all that is coming to us, we have learned to circumvent the ladY. No woman need be as ugly a.~ God made her, nor as unattractive as she was born. Drug store complexions can put the Inherited ones to the blush, and any girl who Is willing to take the trouble can ~c· 'lUire a line of lures and graces that will make any bona fide siren tremble for her job. To the girl, then, who wishes to acquire charm, and who !'~peclally wishes to attract men, 1 would say, flr~t, 11tress your f~?min!nlty. T don't mean be namby-pamby and W'*'PY and dishrag~-. without any backbone. That type of woman has gone out of fashion as com• pletely a..s bustles and hoopskirts. No man now would be bored with lhe sort of perfect lady hlR grandmother was. But the eterna'l feminine remains stlll the eternal attraction for men, and the more womanly a woman Is, the gentler, the tenderer. the sweeter, the more she appeals to men. It you will notice when a man speaks of the woman he loves, he invariably calls her "little'' no matter if she is six feet high and weighs 200 pounds. What he means Is that she gives him the reaction of depending upon him, of looking up to him and that In some subtle way she flatter" his vanity by givIng him the sense of masculine superiority. You never see an aggressive, double-fisted woman, who fight! her way like a man, get anywhere. And In his soul every man adores frills 13.nd furbelows, and like to see women dolled up. That is why girls make such a terrible mistake when they ape mannish ways, and wear mannish clothes. When a girl puU! on knlckerbockers she throws her trump card Into the discard. To the girl who wishes to acquire charm I would also whisper this secret: Make of yourself a mirror In which other people look upon themselves. Especially let men see a flattering reflection of themselves in your eyes. Can your own personal vanity. Listen with bated breath while other people tell you of their exploits, but never mention your own. Enthuse over their cars, their dogs. Marvel at their adventures. Sympathize with their disappointments. Give the glad hand to their successes, and you will be universally regarded as a woman of perfect taste, wonderful insight, profound judgment, a brilliant talker and a companion of whom one could never weary. It is the tireless listeners, and not tile endless talkers, whom men take out to dinner. I' OW. Furthermore-but that Is another story we will discuss tomor- DOROTHY DIX Copyright, 19:l4, by Public Ledger Company VNnO~VO HJ.~ON 'AJ.IO NOSA~8 .::fO NMOJ. SNII'V':i!J.S ' )4 ' I >UI3,0 'A :nNOO ' .L 'M NY ... WIYH-;:) ' J.itYHd~)f 3-:lVI:IOH N3WH301\' .:10 OH\'09 ~OAV~ CHARM. \'ha t Pl ea ~ es I D h D I\ Yomt n E tsiJ.· l t • \ \ "on .1n 1J An) La-~-~-9-ies __ -'l_ •• _'OTO Y IX I , ,~,:~:· ~·;;~, .. Women Are Less Critical of the Opposite Sex Than Men Are-Any JW.an Can Be tl F ascinatot· Who Is Neat and Clean in Appearance, Who Has Good M anne·rs and Who Carries a Sideline of Brains A young man writes: "You have salcl n Jot latelv about charm in women antl toltl iht' ;::iris ho\,. to pleHRP th!' mf'n.· Please put ) ou1· alivit·f' lntn r<·Vf'l"S{· ;::Par nnd tPll what is c:h>1rm in a man and how nwn cnn mak(• a killing with the gil"ls." \ Yell, •on , thnl's ea•y g·oing, for >vomen are not ns hyp e r critical of mPn as mf'n are of women. ·v\Tornen do not dom:<n<l nll iltf' ])f'rf<'<:'tions of men that men rlrmand of women. Any nH~n can he a faflcinator with nne-thousandth 1)art of lhf> natural ;:-ift!-1 1hnl "- womnn ha~ to hav<' anrl a millionth part of th<> C'ffort that sh(' h as to p u t forth to gC't hersC'lf nut of thP " a lso-ran·• _c tns;. nnd m11ke men notice that o;;he is on the nwn. Of coursu, ju~t n.~ thf>l'<' are women ·who at·e born with the COJUe-hither look in their eyes that n1akes every man they meet want to get up antl fo llow them, so t h ere are ml'n b.orn with a way with t hem t h nt no woman cnn resist. It is not o!" these that we are .spealdng, b u t of the common or !;(arden vnl"iflty of youth, who re<~.lizes that he 's no h e-vamp, )Jut who would like to !wow what sort Coot to carry when he steps out among the fair ~ex. Nntm·ally son, the first thing that n woman nnti<-Eh; nbout a man is his appearance', and shl' iR attractocl ot· repul;;ed by that. This does not mean that to altract the man mus h<' n GrN•k g-od, for women do not put the icliotic ya lur> on physicn 1 h <\t!t)' that men c1o. JL is to the overlaf<ting- credit of women I hat "·hile men fnll for the baby-doll type of )\'Omen , women f;Corn her twin hrot(lf'r, the ~tore-dummy sort of nwn. Therefore it doesn't matter whether a man hn.s lal'gP. coulful l'yes, a ('lassie profile and n re:uly-madf' f'iOlh<'s nrly ertl~emf' n t figure or whether he has carroty hnir and a filN' that i~ just an nssemblo.g<' of fPatur<'s. But he mnst he "nicP looking-." 't'hat me,u1s, J)l'imaril;·, clean. Tub]'""· l'<f'ruh1H'<1 Shnven nnd shorn. Vliell pressed. No woman e,·et· fPll in love a sight with n. slovenly, sloppy, slouchy man \"ilh H th I"E'<' cJa;·s ' growth of be·1rcl on his face and who needed a hn i1· eut. "('ostly thy raiment as ll"\Y purHe can bu;·," son, wlH•n you go 1-courting. J<~unny that men. \Yho know hO\Y mu1·h ~;t reRs \'o·nc n put upon clothes, ntWPI' ><eem to think that they notice the wa;· mf"n 1ress. But th0y do. l\fany i1 mnn lost•:< out with a gil"l l>ecau~e he \'Pars baggy trousers and coats that are too short in thP siE>P\'f'S, and the wrong sort of shirts and collars and tics. \Vhen a woman nppears in public with a man ~he likes him to be so stunning lool,!ng that he makes th0 other girls ruhb<'r. Clothes malH' the man to a big extent with wonH•n. ~o us n first .Hl to charm see!-:: the expert services of a n1ilor :mel n haberdasher. The next thing that woman notice about a man is his ntanner~. Not without rf>ason are the villains of melodrama nntl the JnOYies always 1 epresented ns polished men of the worl<l. \Vomen ;ll"c fa~cinater! by the man who is mastPr of even· situation; who )HIS tnct and ~uavity; who nlways ~ay« tl10 right thing ancl dqes the right thin~; who knows ho\" to o1·<l0r a cllnf\er nncl Hn<l a taxi; who cnn take can• of them in a f'rowd; who doesn't ><tep on their feet when he dances, ancl w h o neithf'r bullies B<'rvanls nor cringes he-fore t.hc>m. 011 the other hand women loathe men who IHP lH>nrish in man• ter, who are awlnvard and ill at ease; who nt"vee know what to ~'tY when they meet strungerf', or whieh fork nnd spoon to u:oe at lh~ tab!C', and who ne\·er go nny"·hcre without ~;etting into rows with taxi drivC'r~. and theater ushers, and waitPt·s at rcstaurnntR. _ ·ot;1in;o;. not m·en h<dng n.,mo!lf'l of all the virtues and a wizard at moncymakin:::-. atones in a "·oman·~ eyeR for n man C'~tting soup aurlibl;-·. I strongly advise any young man who haR not harl rigorous homn training in etiquE>t t£>, or many social auvanlages in hiR up-bringing, to pick odt the most Plega]lt man of his acquaintance and carefully undf'!•study h!R manners. The n ext thing that attracts n. woman to n man is th" line or converHa tion he carries. Men admiee the beautiful hut clumh women. but wonwn have no u Re for handsome moron~. They like brains on th" side. They admire the man who haR something to s:1y and who knows how to say it. They like jolly, amusing men, and men who can tl)rn a deft compliment. But they are bored to tears by thE' egotists who monologu" hY ell(' hOUr flbOUt tJH'mSeiYE'S, ancl how gTE'flt and WOndPrfuJ (hpy <ll'C, and how the girls arc- all crazy a hout them. and what a ma1·velous ca1· they have. ancl ho\ many miles they have made .• \nc1 l110:> g-<'t sick and tired of. lhe 111;111 who grouches around whE>ne,·er an.vhor1y r ise romes to call. and \·ho ha~ lo alwnys he pelted and r·odcllecl to keep him in a good humor anti J>revcnl lim fronl acl ing like a spoiled baby. 'T'hP)' <l<'sp!Re lh<' tightwad who comeR anrl PHtR up th0ir food. ancl camps on their f'hairs and ta.i{('S 11p theit· tinw, anrl who n0H'l' tak<'s them out anywlH•re that .. osl " p0nnr. l~ul thny lHH'fl a c·ontrtnJ.>t for t he man who lei~ ll1f'm \'OL'k him :wtl wh<J :-prnrls more til Jn he can afford. Xicc ;:;ir!R are nnl. gnlrJ-rJig·gpr~. X<'ithrr '<rr thr~· nkkrl nut·ser~. f'O '\hen ;rn1J tak<' a girl out mal<c her ft'Pl th:et it gives you p!Pa,;urr tu 1iJlClld yout· mon0y on her, IHtt <>lHo Jet her rt>aliz<' tiHit ;-•ou an> no ca~y mark. Tn de:tlip;r wilh wonH'n he bold; be not ton holrl. \Vomrn lii;P mAp who are neithc,,. l're~h llOJ' <tfnlicl. 1'hey likr to lhinl< that :1 111an f'tancls a little in awr of 111<'111, hul tbcy clon't \i\lll him to be so awe-struck that they h<J\'C' to tlo <1ll the courting. Perhaps these few suggestions will he \lf'lpful to you, :<on: loul, as I said 111 the beginning, women arc not har •. l to ]!lease. 1\n~ l!Hlll can do it. DOROTHY DlX Copyright. 19~4. hy Public Lcd!'P.I' Company. VNnO~VO H~~ON 'A~IO NOSA~8 .::10 NMO~ SNII'It3.LS '}t 'I ~><3,::> 'A:lnNOO '.L 'M NY.-.WIYHO • ~tiVHd31)1 30VMOH N31r\11:1301\' .:!0 01:1\'08 swvn,IM 'd ·o HOAVII'I CHARACTER - Cold, Contemptuous,. q:-~- John Quincy Adams, harsh , thorny, socially repellant, friendles s , with icy contempt or white-hot scorn or nearly all around hmm . His life a solitary and contemptuous gladiatorship . Warner, Lib ., I, 134 . Compare Ue f rigid calculation of his 11Mission of America" with Benton's generous outbursts . (~ ~ ........,t.t4-.~ 'R~;-..l..-~·) ~~· ~~~. b:2~. COLDNESS. ( 'HARVARD COLDNESS EXPLAINED BY TRAIN Author Admits " Indifference" and Asserts It Is Due to Influence of Puritans. lBUT DENIES S~OBBISHNESS Urges Simulation of Greater Geniality for Occastons When " Barbarian" Uses Word "Snob." "Now this reluctance to give one's neart away (or, l perhaps should say, to let anybody )<now you have one) has its intellectual concomitant In a reserve of Judgm0nt and a detached impartiality that savors of coldness. But It is r.either ~nobbl11hne~s nor priggishness, although it may easily become either o1· both, in which ev<•nt it certainly Is not cudearlng. Therefore, it. >~eems to me that the Boston man who (like myself) was graduated from Harvat·d can afford to laugh good-naturedly at the allegation that he is· ' like an egg which has been hatched twice-each time successfully,'