Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

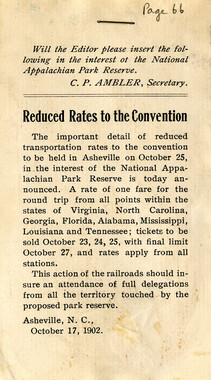

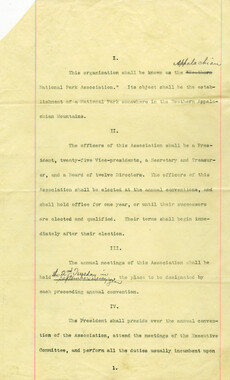

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Champion Fibre Company (5)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (23)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (17)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Stearns, I. K. (2)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (45)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (55)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (72)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1810s (1)

- 1840s (1)

- 1850s (2)

- 1860s (3)

- 1870s (4)

- 1880s (7)

- 1890s (64)

- 1900s (294)

- 1910s (227)

- 1920s (461)

- 1930s (1501)

- 1940s (82)

- 1950s (15)

- 1960s (13)

- 1970s (47)

- 1980s (14)

- 1990s (17)

- 2000s (31)

- 2010s (1)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (80)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1)

- Avery County (N.C.) (6)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (145)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (204)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (10)

- Clay County (N.C.) (3)

- Graham County (N.C.) (108)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (416)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (263)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (13)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (58)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (17)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (8)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (25)

- Madison County (N.C.) (14)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (5)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (7)

- Polk County (N.C.) (2)

- Qualla Boundary (22)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (16)

- Swain County (N.C.) (513)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (36)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (2)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (34)

- Aerial Views (3)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (4)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (77)

- Drawings (visual Works) (174)

- Envelopes (2)

- Financial Records (9)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (34)

- Guidebooks (1)

- Interviews (11)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (219)

- Manuscripts (documents) (91)

- Maps (documents) (69)

- Memorandums (14)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (20)

- Negatives (photographs) (198)

- Newsletters (12)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Photographs (1657)

- Portraits (36)

- Postcards (15)

- Publications (documents) (107)

- Scrapbooks (3)

- Sound Recordings (7)

- Speeches (documents) (11)

- Transcripts (46)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (198)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- George Masa Collection (89)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (126)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Jim Thompson Collection (44)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Map Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (10)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (107)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Appalachian Trail (19)

- Church buildings (9)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (91)

- Dams (20)

- Floods (1)

- Forest conservation (11)

- Forests and forestry (42)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (64)

- Hunting (2)

- Logging (25)

- Maps (74)

- North Carolina -- Maps (5)

- Postcards (15)

- Railroad trains (8)

- Sports (4)

- Storytelling (2)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (39)

- African Americans (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

- Sound (7)

- StillImage (2088)

- Text (655)

- MovingImage (0)

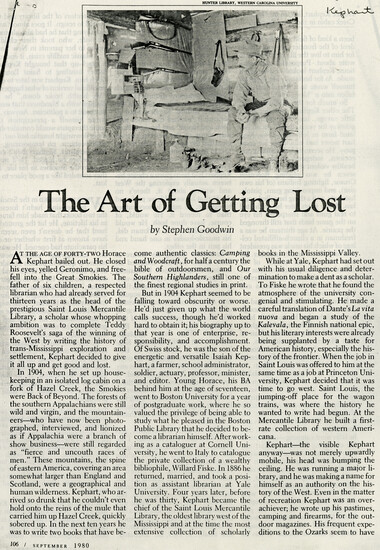

The Art of Getting Lost

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

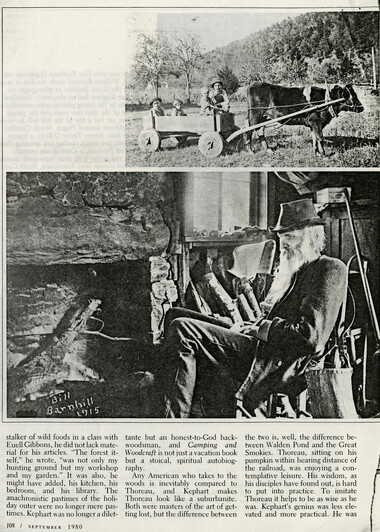

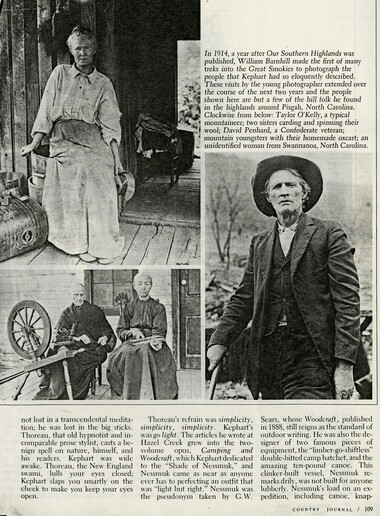

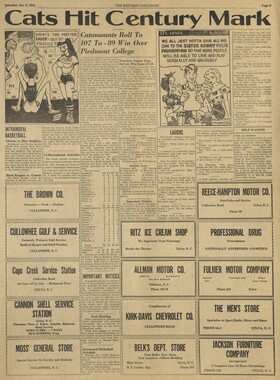

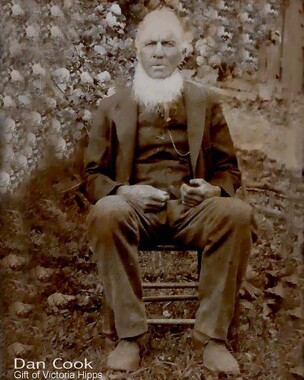

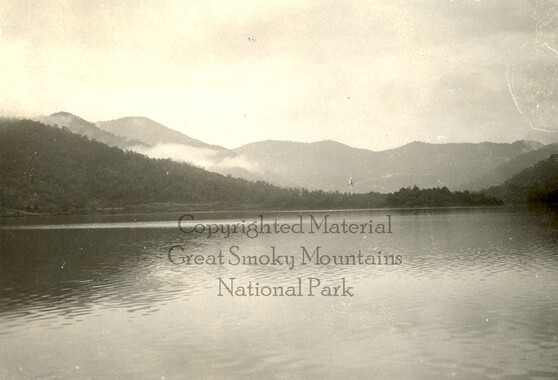

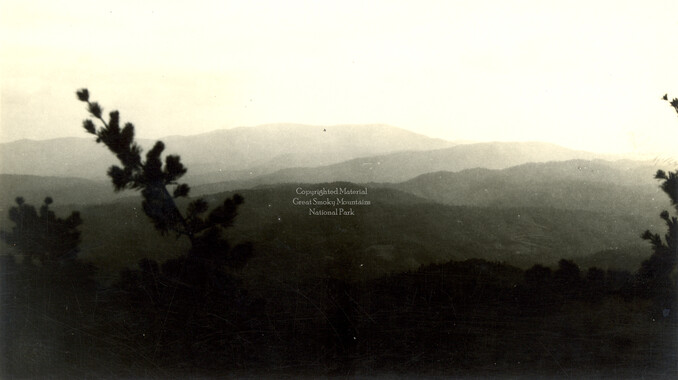

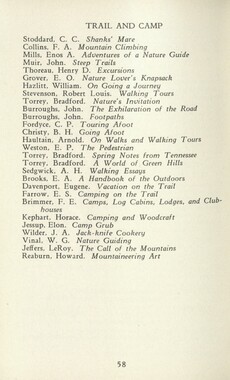

HUNTER LIBRARY, WESTERN CAROLINA UNIVERSITY MiiNaS,f::i- I \~B~*p UuX-J^-» The Art of Getting Lost by Stephen Goodwin At the age of forty-two Horace xV. Kephart bailed out. He closed his eyes, yelled Geronimo, and free- fell into the Great Smokies. The father of six children, a respected librarian who had already served for thirteen years as the head of the prestigious Saint Louis Mercantile Library, a scholar whose whopping ambition was to complete Teddy Roosevelt's saga of the winning of the West by writing the history of trans-Mississippi exploration and settlement, Kephart decided to give it all up and get good and lost. In 1904, when he set up housekeeping in an isolated log cabin on a fork of Hazel Creek, the Smokies were Back of Beyond. The forests of the southern Appalachians were still wild and virgin, and the mountaineers—who have now been photographed, interviewed, and lionized as if Appalachia were a branch of show business—were still regarded as "fierce and uncouth races of men." These mountains, the spine of eastern America, covering an area somewhat larger than England and Scotland, were a geographical and human wilderness. Kephart, who arrived so drunk that he couldn't even hold onto the reins of the mule that carried him up Hazel Creek, quickly sobered up. In the next ten years he was to write two books that have be- 106 / SEPTEMBER 1980 come authentic classics: Camping and Woodcraft, for half a century the bible of outdoorsmen, and Our Southern Highlanders, still one of the finest regional studies in print. But in 1904 Kephart seemed to be falling toward obscurity or worse. He'd just given up what the world calls success, though he'd worked hard to obtain it; his biography up to that year is one of enterprise, responsibility, and accomplishment. Of Swiss stock, he was the son of the energetic and versatile Isaiah Kephart, a farmer, school administrator, soldier, actuary, professor, minister, and editor. Young Horace, his BA behind him at the age of seventeen, went to Boston University for a year of postgraduate work, where he so valued the privilege of being able to study what he pleased in the Boston Public Library that he decided to become a librarian himself. After working as a cataloguer at Cornell University, he went to Italy to catalogue the private collection of a wealthy bibliophile, Willard Fiske. In 1886 he returned, married, and took a position as assistant librarian at Yale University. Four years later, before he was thirty, Kephart became the chief of the Saint Louis Mercantile Library, the oldest library west of the Mississippi and at the time the most extensive collection of scholarly books in the Mississippi Valley. While at Yale, Kephart had set out with his usual diligence and determination to make a dent as a scholar. To Fiske he wrote that he found the atmosphere of the university congenial and stimulating. He made a careful translation of Dante'sLa vita nuova and began a study of the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, but his literary interests were already being supplanted by a taste for American history, especially the history of the frontier. When the job in Saint Louis was offered to him at the same time as a job at Princeton University, Kephart decided that it was time to go west. Saint Louis, the jumping-off place for the wagon trains, was where the history he wanted to write had begun. At the Mercantile Library he built a first- rate collection of western Americana. Kephart—the visible Kephart anyway—was not merely upwardly mobile, his head was bumping the ceiling. He was running a major library, and he was making a name for himself as an authority on the history of the West. Even in the matter of recreation Kephart was an over- achiever; he wrote up his pastimes, camping and firearms, for the outdoor magazines. His frequent expeditions to the Ozarks seem to have

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

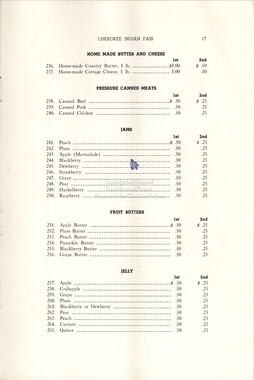

This 11-page article titled, “The Art of Getting Lost,” is about the life and work of Horace Kephart. It was written by Stephen Goodwin in 1980 for the magazine Country Journal. The article features photographs contributed by Western Carolina University’s Hunter Library and includes an excerpt from Kephart’s book “Camping and Woodcraft.” Horace Kephart (1862-1931) was a noted naturalist, woodsman, journalist, and author and promoter of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

-